How To Design An Experiential-Learning Activity, Game, or Simulation

What should the learner do?

That is the key question I ask when designing an experiential learning activity, game, or simulation.

Notice the "do".

This is different than when designing a textbook, video, or page-turn elearning. With these types of conventional learning resources, the question being asked is this:

What should the learner know?

"Know" is very different than "do".

"Know" leads us to create a list of content items to be covered in the learning. The content is then created and presented in its required form (book, video, elearning, etc). Some type of assessment, like a quiz or basic activity, may also be included to confirm that the learner has reviewed the material.

It's all basically a list of things to know. Experiential learning is different.

Learning By Doing

Experiential learning is often called learning by doing.

We must design what we want the learner to do — to achieve the desired learning outcomes or behavioral change.

But, before we address this question, there are 5 other steps we must first process to understand our instructional goals, learner profiles, time, level of effort, and methodology. I describe these 5 steps in a previous issue of this newsletter — The First 5 Things I Do When Designing An Educational Experience

After completing those 5 steps, we are ready to tackle the big question!

What should the learner do?

To illustrate how to answer this question, I'll use examples of real products I've created.

Let's say I want to teach the learner how to run a business.

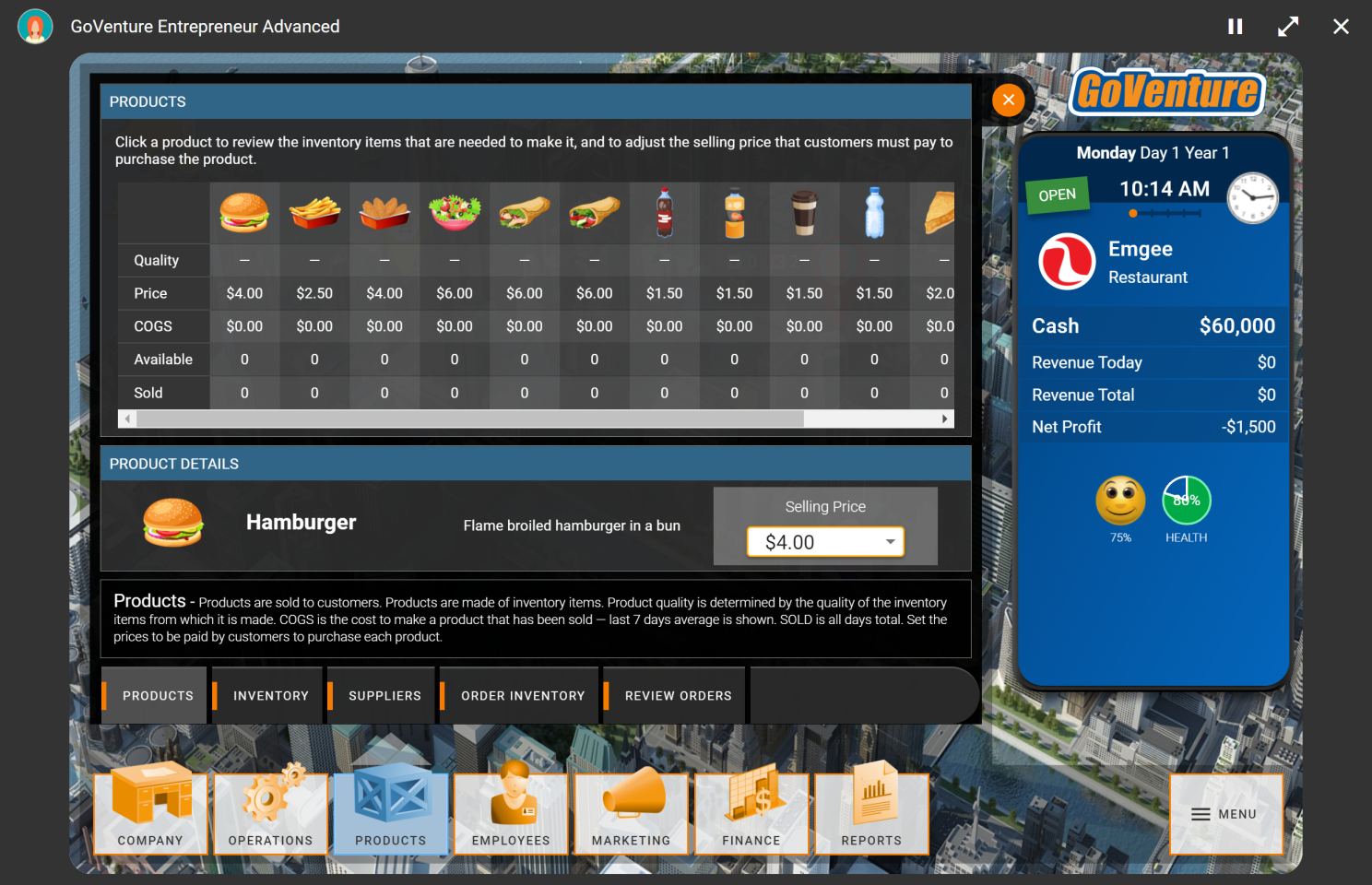

Then I will have the learner run a business — like the restaurant simulation shown below. The learner manages a menu of products, sets prices, manages inventory, hires and schedules employees, and more.

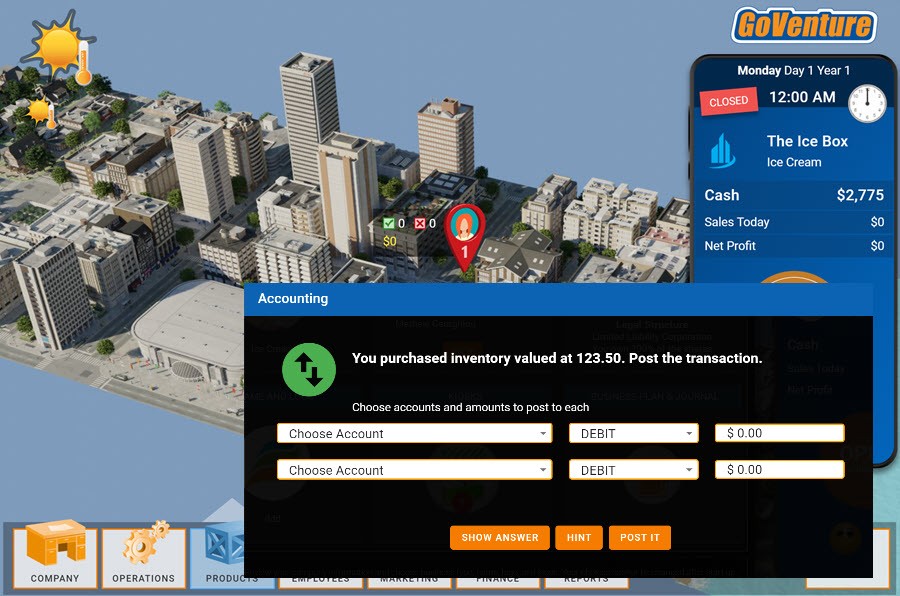

If I want to teach accounting, I have the learner experience accounting in the context of running a business — perhaps the same business as above. I start by guiding them to discover the purpose, importance, and value of accounting. Then, I have them follow the methodology of how accounting is done. I may also have them post debits and credits, like the accounting window shown below.

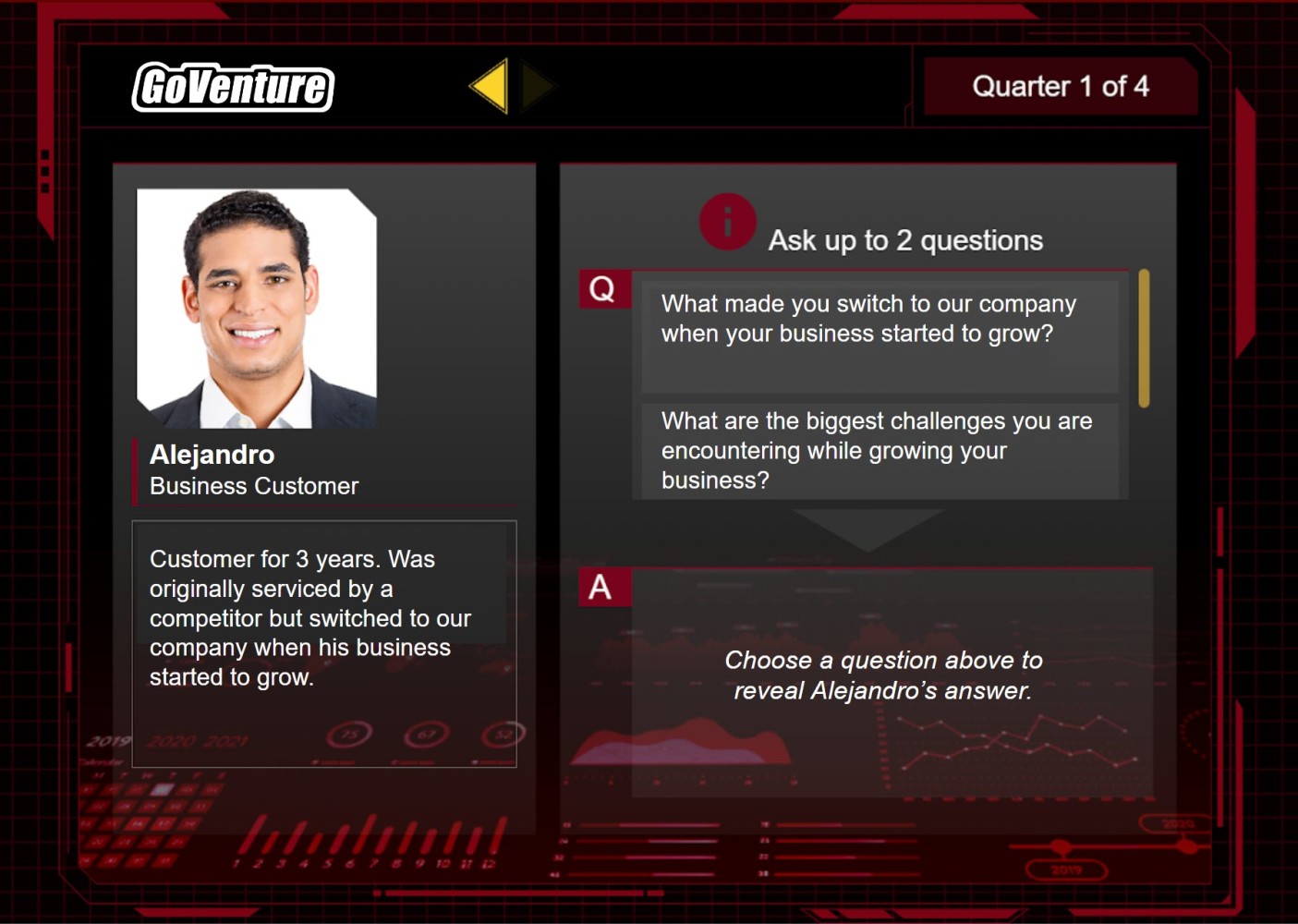

If I want the learner to improve their ability to ask good questions, I put them in a situation where they must ask questions and assess the responses. Below is a leadership simulation where the learner gathers information from various simulated stakeholders in order to make evidence-based decisions. This example uses a business theme but I also designed a scenario with a space theme.

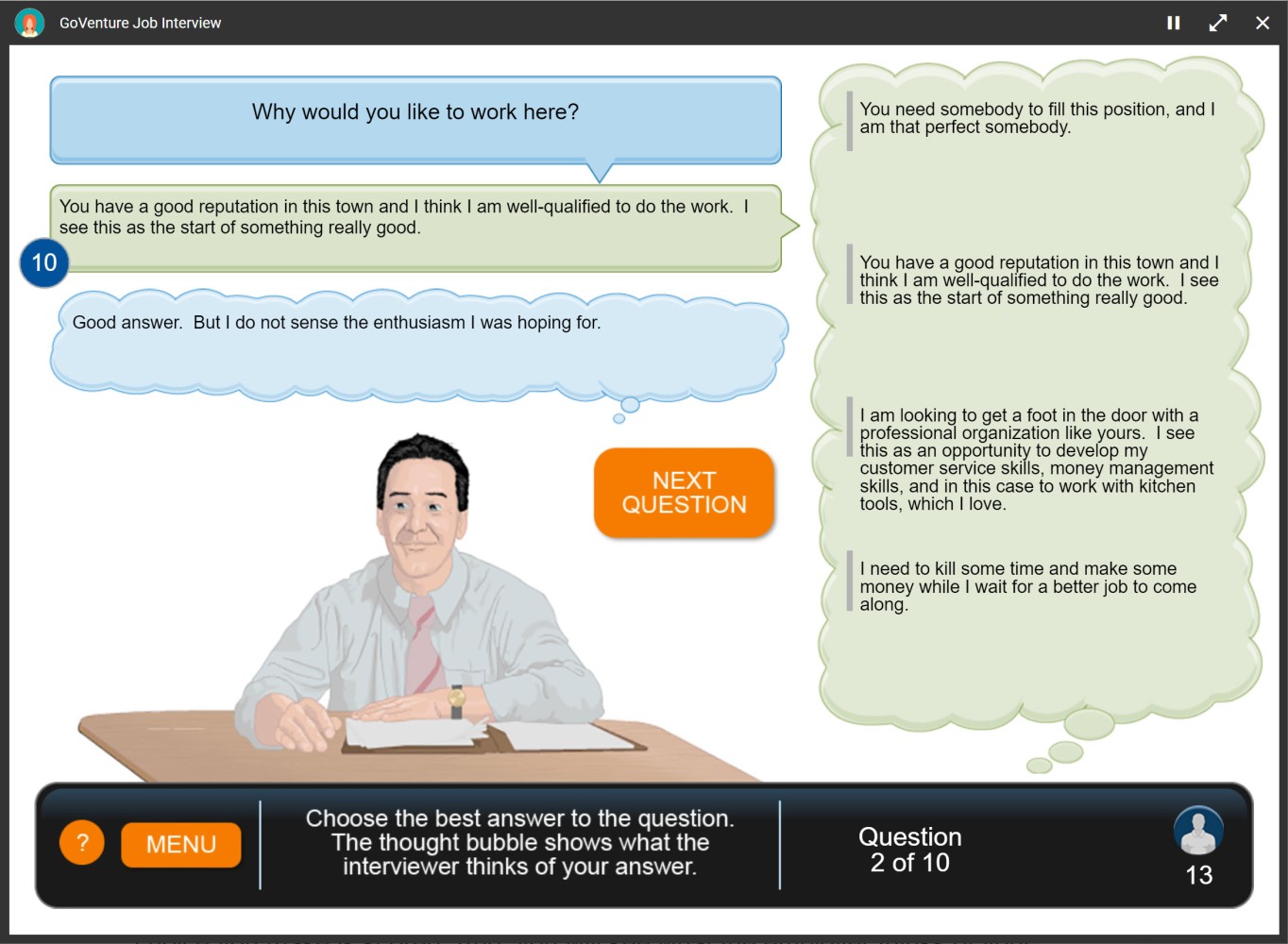

If I want the learner to improve their ability to answer questions, such as in a job interview, I put them through a simulated job interview process. Shown below is a job interview simulation where the interviewer asks a question and the learner chooses a response. The response is scored and the interviewer discloses what they think of the response, revealing important feedback to guide the learner.

The examples shown above are mainly software simulation games, but the same design approach can be used when designing live role-playing scenarios, board games, virtual reality explorations, and other types of activities.

If you have trouble visualizing what you want the learner to do, then look at it from a different perspective and ask yourself this question— What problem should the learner solve? Then put the learner in a scenario where they have to solve the problem.

Literal or Metaphor?

Once we decide on the main activity for the learner to do, the next consideration is whether we want the environment to be literal or based on a metaphor.

For example, we could take a literal approach and have the learner run a real business, similar to McDonald's, Wal-Mart, or Tesla. Or we can use a metaphor where the learner is doing business with aliens in space.

Which approach is better? It depends on the first 5 steps I mentioned earlier in this article.

Theme?

Theme is also a factor in the design decision.

With a literal approach, we could design the experience based on present-day Hong Kong or a Texas western from the 1800s.

With a metaphor, we could simulate working within a colony of ants.

Imagination is at play here — but bridled to make sure that the instructional objectives and learner profile are always considered.

One Main Activity With Subactivities

Once the main activity and theme are chosen, the next step is to identify the subactivities to be integrated within this main activity. These subactivities make sure the learning experience covers everything necessary to achieve our instructional outcomes.

This is somewhat equivalent to drafting a list of content items that I described earlier when creating a textbook, video, or page-turn elearning. But, with experiential learning, we are designing activities for the learner to do, not just content to know.

To illustrate this concept, I'll use the Food Truck Entrepreneur Board Game that I recently designed.

My objective with this educational game is to help youth and adults learn the very basics of running a business.

I chose a literal environment of running a realistic business in a present-day city.

I chose the food truck theme because it's a micro business that is easier to understand and the mobility of the truck adds a fun game dynamic.

So the main activity here is running a food truck business. For the subactivities, I want the learner to do the following:

Move a truck to different locations in the city.

Compete with other food truck businesses to win customers.

Earn rewards for selling food to customers who prefer a specific type of food.

Manage product inventory.

Earn money and pay bills.

Win by earning experience points (XP).

There's much more to the experience, but as you can see from the short list above, the key learning outcomes of running a business become revealed through the gameplay.

Filling the Gaps

One of the challenges with designing experiential learning is that it's much more difficult to create than conventional learning. And so it requires much more effort, skill, and budget — perhaps 10 to 100 times more.

This means that it's not always feasible to deliver learning content in this way. That's where text, graphics, and video can be used effectively. Not as the main activity, but as subactivities or supplemental resources.

When I have a lot of content I need to deliver as supplemental resources, my current preference is to use one of these methods:

Microlearning — Short video, followed by summary text for reflection, followed by a short activity or quiz. I describe this in detail here — Converting a Book Into Microlearning Modules

Narrative Story — Using text, I guide the learner through their own personal story and journey of discovery. I describe this in detail here — How to Design a Narrative Story For Experiential Learning

Feedback

A key component of experiential learning is feedback. Every decision a learner makes should have a visible consequence. Indecisions should also have consequences. This has to be integrated into the gameplay.

Many decisions may have both negative and positive consequences. This forces the learner to consider the complexities of the real world, where the best decisions are not always easy to identify.

Sometimes, the consequences are revealed immediately, while others might be revealed later in the gameplay.

Often, we need to accelerate and exaggerate consequences so that they are more visible. Because a consequence that is too subtle to be noticed won't influence learner behavior.

Repetition

The gameplay design should consider how to allow the learner to repeat the primary and subactivities many times. This rote method of learning can be very powerful in building the muscle memory of the brain. I've written about this in another issue of this newsletter — Rote Learning Builds Your Brain's Muscle Memory

Progression

When designing activities that offer deep learning, consider how to include progression in the gameplay. Progression allows the learner to take on challenges that increase in difficulty as the learner gains new skills and demonstrates competency.

Without progression, the learner may get frustrated early on if the gameplay proves to be too challenging.

Reflection

Reflection is an important exercise to include with experiential learning. Allowing the learner to reflect on their experience triggers connections to be made with the decisions and consequences experienced in the activity, while adding context for personal real-world alignment.

One of the best ways to accomplish reflection is for the instructor to host a debrief session. During the debrief session, the instructor makes observations on everyone's performance and asks questions to trigger discussions.

Participants listening to the discussion learn from each other while reflecting on their own personal experiences.

I describe reflection and coaching in this video — An Instructor's Role Changes to a Coach When Using a Simulation

Assessment

When designing a learning activity, we must consider how the learner will be assessed. Did they complete the activity? How well did they do? Did they gain specific skills or competencies?

Assessment in experiential learning, particularly with games and simulations, is based on actions and results. Results are based on demonstrated behaviors, skills, and performance — not just knowledge or memorization.

This is powerful because:

Assessment is more authentic and accurate.

Assessment is personalized.

Assessment is less prone to cheating.

Assessment may be automated for both students and instructors.

Learners can monitor their own performance in real-time and improve if needed.

Eliminates the anxiety triggered by high-stakes tests and waiting for grades to be revealed.

Bringing It All Together

Consider how we might teach someone to ride a bicycle.

Certainly, we would not start by having them read a book or listen to a lecture. We might have them watch someone demonstrate how to ride a bicycle — live or on video— as long as it's brief and focused on the basics (or on how exciting it may be to ride a bicycle).

We intuitively know that the only way this is going to work is to get the learner on a bicycle right away. They have to experience riding a bicycle in order to learn how to ride a bicycle.

Riding the bicycle is the main activity.

The subactivities may include how to maintain balance, how to pedal, how to stop, how to take turns, and how to change gears. All designed with progression in mind to keep the rider safe and engaged from start to finish.

We'll have the learner repeat all of the above many times to build muscle memory.

We'll occasionally pause and reflect on what has been learned, individually and collectively.

Once the learner has directly experienced how to ride a bike, they are now ready for more. To fill in the gaps, we may then provide videos, books, and lectures on how to ride a bicycle more efficiently, or how to repair a bicycle, or build muscle mass for high performance.

And we'll assess the learner by having them ride a bicycle along a path that demonstrates their skill and competency.

Success!

Receive this newsletter by email —

I'm Mathew Georghiou and I write about how games are transforming education and learning. I also share my experience as an entrepreneur inventing products and designing educational resources used by millions around the world. More about me at Georghiou.com